Minted In Prague at Czech National Bank’s Money Expo

Money, money, money. No, I’m not talking about the Abba song, but the path along which money has travelled stretching as far back as civilization itself. And, as I discovered on a recent trip to Prague to visit the ‘People & Money’ exhibition, there is a Czech saying that goes: “Money is the means of the wise and the end of fools.”

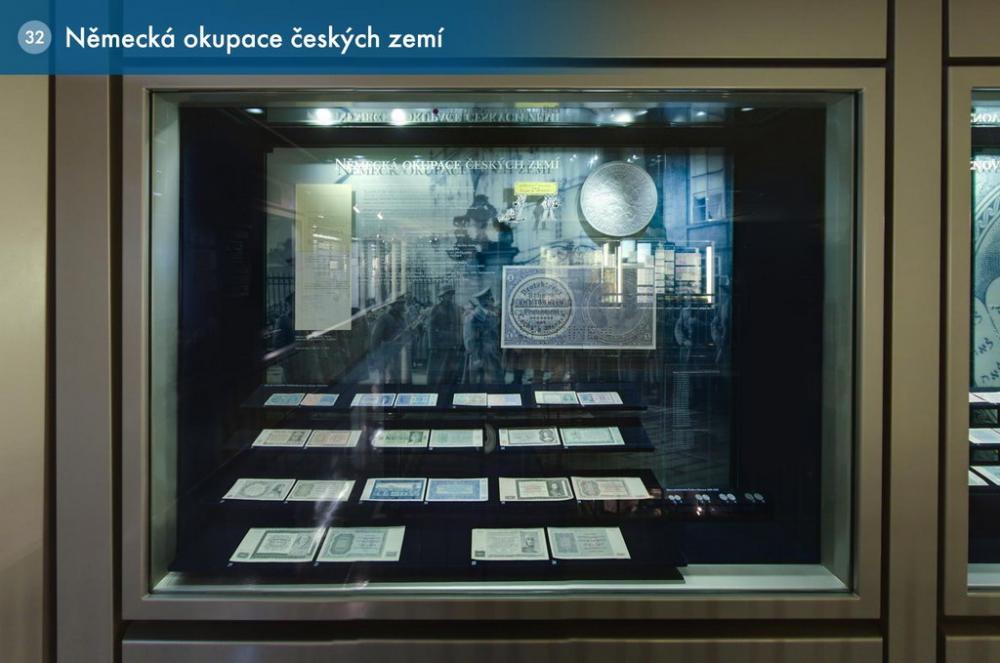

The first paper money ever used in Czech territory (1762), how the Bohemia thaler gave its name to the U.S. dollar, the first Czechoslovak banknotes, and a heavyweight gold coin to commemorate the stabilization of an independent Czechoslovak currency in 1919 and the idea of restoring the gold standard, are some of the highlights at the exhibition in the Czech National Bank (CNB) in Prague.

With 65 display cases on show in the former strong room at the central bank, which covers the pre-1918 period to the present, one can see that much thought has clearly gone into the presentation of exhibits. You can also get a feel for money having been “a good servant and bad master”, another Czech saying.

Putting on the exhibition involved a team effort that included a committee of experts from the CNB and elsewhere, headed up by a member of the Bank Board. Initially opinions had varied on what the underlying concept to the project should precisely be.

Professor František Vencovksy at the University of Prague, writing in a forward to the exhibition catalogue, asked: “Was it to be a history of money, a history of the central bank, or a history of banking and finance in general. Or, was it to tell the story of the Czech, or Czechoslovak, state?”

He added: “It was ultimately decided that the exhibition should cover the development of the currency in this country whatever the political and economic situation.”

On my visit this June to the exhibition I was fortunate to be guided around by Jakub Kunert, the CNB’s chief archivist, and his colleague Irena Trojanova. Given the breadth of artefacts on display I was asked what I was particularly interested in seeing, which proved a sensible move as you would probably need to make several trips to cover all the bases.

Gold Standard Remembered

Descending into the former strong room of central bank you cannot fail to see a heavyweight gold coin on display. Weighing in at 130.24 kilograms and measuring 53,5cm in diameter by 4,8cm thick, this huge coin has a nominal value of CzK100,000,000, a purity of 999.9 and a work that is “unparalleled in modern Czech minting” according archivist Kunert.

The work, which is the largest gold coin in Europe and the second largest in the world, reflects the origins and stabilization of an independent Czechoslovak currency, which was originally associated with the idea of restoring the gold standard (currency), as used in the Austro-Hungarian empire until World War One. As such it is symbolic of 100 years of the Czech-Slovak crown.

In order to produce the massive gold coin, the Bank organised an anonymous procurement process for its design. A total twelve designs were considered and in the end analysis a submission from Czech sculptor Vladimír Oppl was recommended.

Castings of two gold discs - one weighing 259kg and a second at 270kg – were undertaken by Metalor Technologies in Switzerland, with the milling (at least 16 operations) of the design achieved from 3D digital scans in Vienna of both sides of the coin from plaster castings. Subsequently the coin was finished off by master engravers in Česká mincovna (Czech mint) for the final flourishes.

First Czech Money

Among other exhibits that caught my eye in the strong room included the first Czech money - silver deniers - an attribute of the sovereign power of the rulers of Bohemia (see Case 3). It is thought that these were struck perhaps as early as in the reign of Duke Boleslav I in the 970s.

With their name derived from the Latin term for coins used throughout Europe at the time (denarius), they were produced in mints located in Vysehrad Castle in Prague and other towns. In 1300, King Vaclav (Wenceslas) II initiate a reform abolishing the denier and replacing it with the ‘gros’ currency, which was based on the much valued silver coin, the Prague Gros (minted in Kutna Hora).

U.S. Dollar Forerunner

A predecessor of the U.S. dollar can be seen in Case 7. The story goes that coins minted in the new mint of noble house of Šlik (Schlick) at Jachymov became known as Joachimsthaler, hence name ‘thaler’, having been extracted from a German expression for valley.

Containing 27.41 grams of silver and being 40mm in diameter, the coin soon spread across central and western Europe. In the Netherlands it was called ‘daaler’ and in Scandinavia ‘daler’. The name in the form of the dollar was applied by the end of the eighteenth century (1792) to the silver monetary unit of the United States.

The Czechoslovak Crown

It was the Currency Act of 10 April 1919 that in fact established the Czechoslovak crown currency (previously known as ‘koruna’, abbreviated to ‘Kc’), stipulating that “one Czechoslovak crown shall equal one Austro-Hungarian crown.” And, the first money issued by the Czechoslovak Republic was a 100-crown government note dated 15 April 1919 (but issued on 7 July 1919 ), with first coins being the 20 and 50 ‘heller’ pieces issued in February 1922.

The archivist, who guided me to Case 12 (‘The Rasin Plan & Currency Reform’), explained that it was Alois Rašín, the first Finance Minister of the new Czechoslovak state (from 1918-1919), who sought to rectify the disastrous financial and monetary position of the nation.

His plan was to turn the Czechoslovak currency into a gold-standard currency. This involved: (1) Separating money circulating in the territory; (2) Creating a national monetary unit; (3) Fostering an increase in the purchasing power of the crown. As a result of the reform, half the cash (notes) submitted were stamped and returned in circulation, while the rest was to be withheld and covered with 1% assignable state bonds.

The Concept to National Bank of Czechoslovakia

A final highlight for me, which was not on show but brought out from a back room by Kunert and carefully contained in a brown folder, were pages from the so called ‘Economic Bill’ (September 1918), which was prepared by Jaroslav Preiss, CEO of Zivnostenska banka (Trade bank) and an economic and business colossus of the early 20’s century, who contributed to making the country into a major industrial player between the wars.

This followed discussions among Czech politicians about the future Czech state, which at that time was called the ‘Czech Empire’. The correspondence also outlined the concept of a central bank, later National Bank of Czechoslovakia prior to its formation.

Entry is free to the exhibition, which is located at Na Prikope 28, 115 03 Prague 1 (nearest metro station Náměstí Republiky/line B), after registering via the CNB’s website (see: https://www.cnb.cz/cs/o_cnb/expozice-cnb/expozice-praha/rezervace/). A video (‘The Czech heavyweight coin’) produced by the central bank can be viewed via this link: https://youtu.be/-RqCG1Et7z4.

Note: During the author's visit to Prague this June he stayed at The Golden Key boutique hotel (see: https://goldenkey.astenhotels.com/en) just next the Prague Castle complex and Strahov Monastery that overlooks the Czech capital. The 4-star hotel, whihc is part of the Asten Hotel group, is located at Nerudova 243/27 and comprises 25 rooms and suites that offer views of Petřín, the Lesser Town and Nerudova Street.

The street was named after a famous Czech poet and journalist, Jan Neruda, who wrote many short stories about the district and lived in the street between 1849 and 1857. Prior to 1770, the houses and the people who lived in them were identified by house signs, Hence, the Golden Key symbol that hangs outside the hotel represents the keys that were made on the premises for Prague castle and other places.

About the author: Roger Aitken is a freelance writer who contributes to a number of titles and was a former FT staff writer. In 2014 he was awarded a press prize from Czech Tourism on the 25th anniversary of the Velvet Revolution.